LIST OF CHARACTERS

OUR ADAPTER — A thief, of sorts; who has found it permissible to condense, to redact, to conflate, to alter tenses (as urgent times require liberties)

OUR NARRATOR — Filthy; riddled with lice; hogs vomit when seen; skin encrusted with the scabs and scales of leprosy; covered with yellowish pus; knows neither the water of rivers nor the dew of clouds; an enormous mushroom with umbelliferous stalks grow from nape (as on a dunghill); has not moved limbs for four centuries; feet have taken root in the ground and form, up to belly, a sort of tenacious vegetation; full of filthy parasites (this vegetation no longer has anything in common with other plants, nor is it flesh); heart beats despite rottenness and miasmata of corpse (we dare not say body); a family of toads has taken up residence in left armpit (mind one of them does not escape and come and scratch the inside of your ear with its mouth, for it would then be able to enter your brain); a chameleon in right armpit perpetually chases them to avoid starving to death (everyone must live)

OPENING SPEECH:

OUR ADAPTER unlocks and opens a door, being and through a conduit for entry (and presented in advance of what will come):

OUR ADAPTER:

We adapt because:

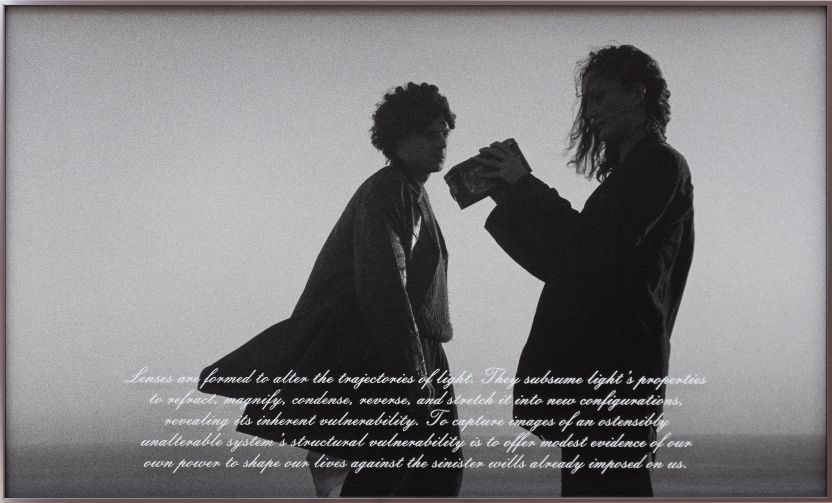

To adapt is to filter the given powers and to reformulate them for uses unwanted and/or unanticipated within the sanctioned functions.

We adapt as:

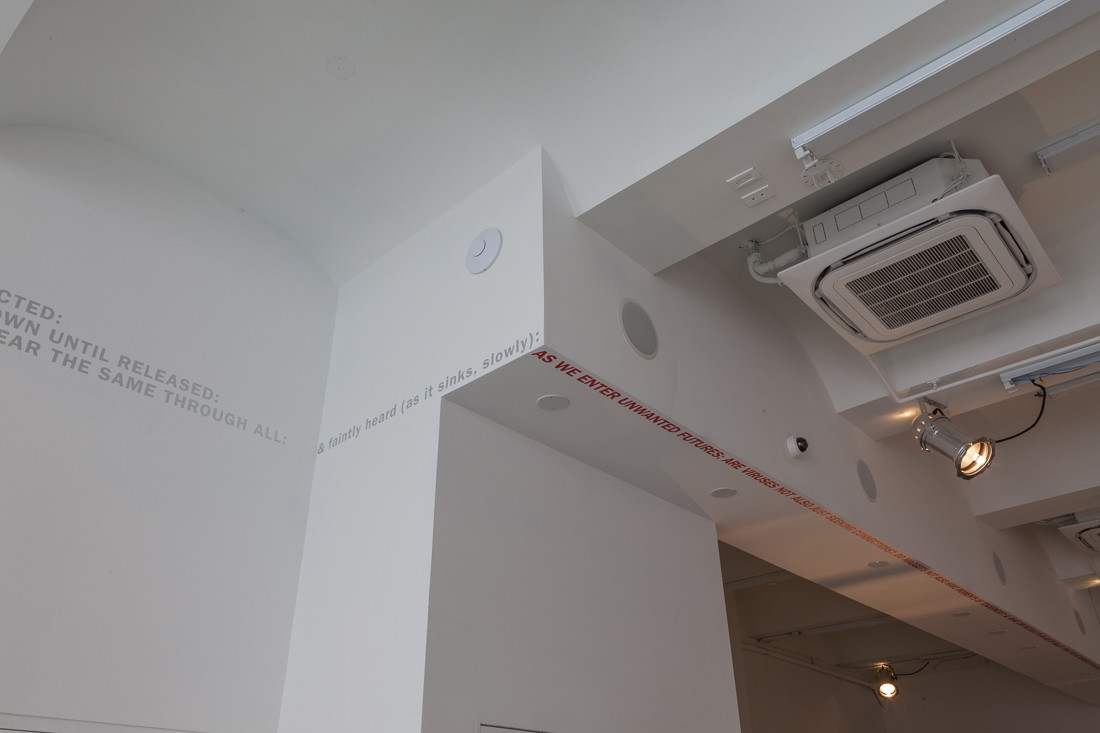

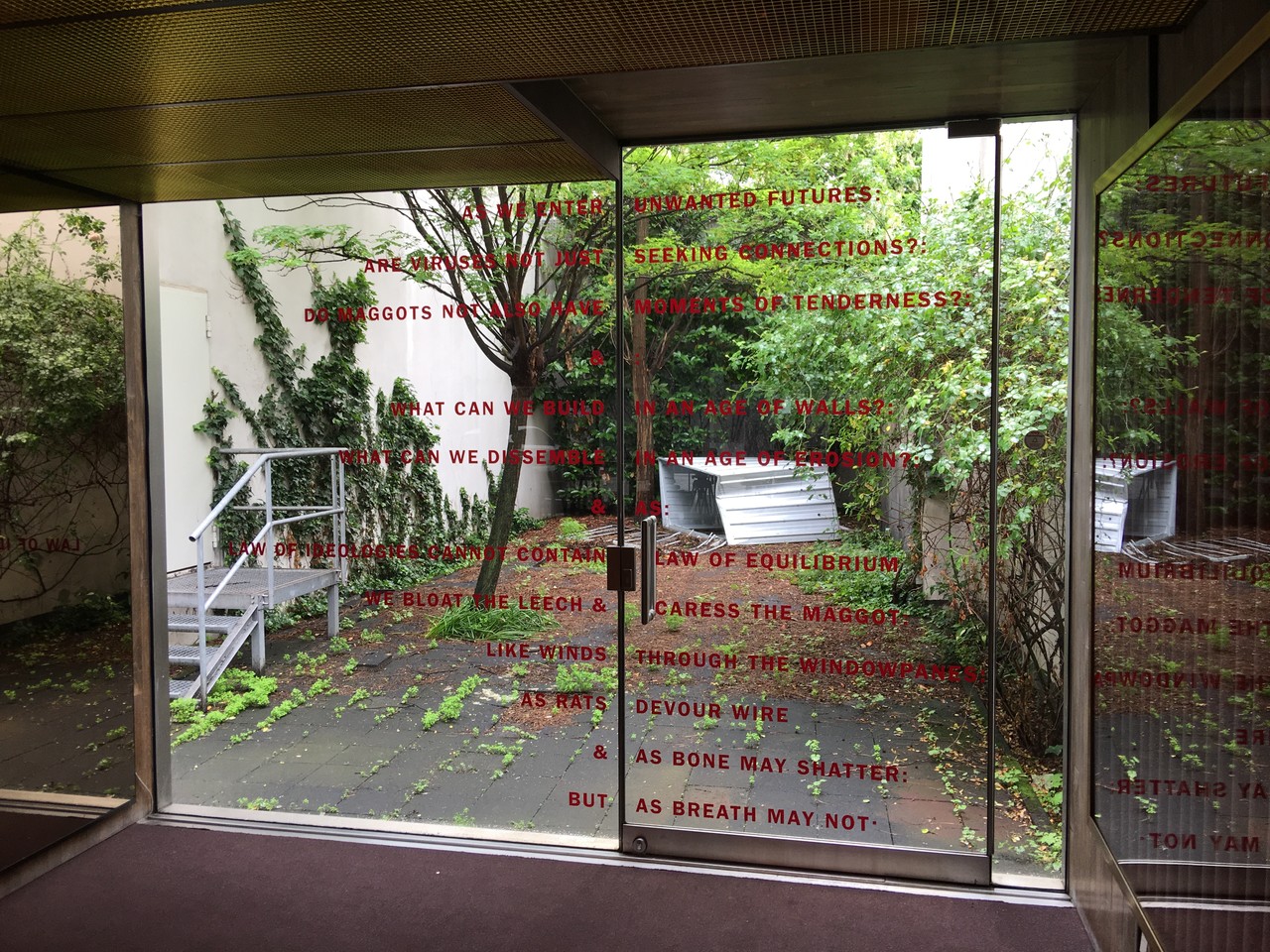

These powers flow through our world like a virus, shifting form constantly and towards immunity, shifting definitions softly and towards impermeability.

We adapt in order that:

We too may change form and:

Like the rats below and the bats above and like the winds which pummel and which flow through all:

Evade and pilfer and grow and infect:

But constructing, with great care, a burrow from which to act

(if there is still enough time to do so & as faint sounds echo further than none).

& IN TIME:

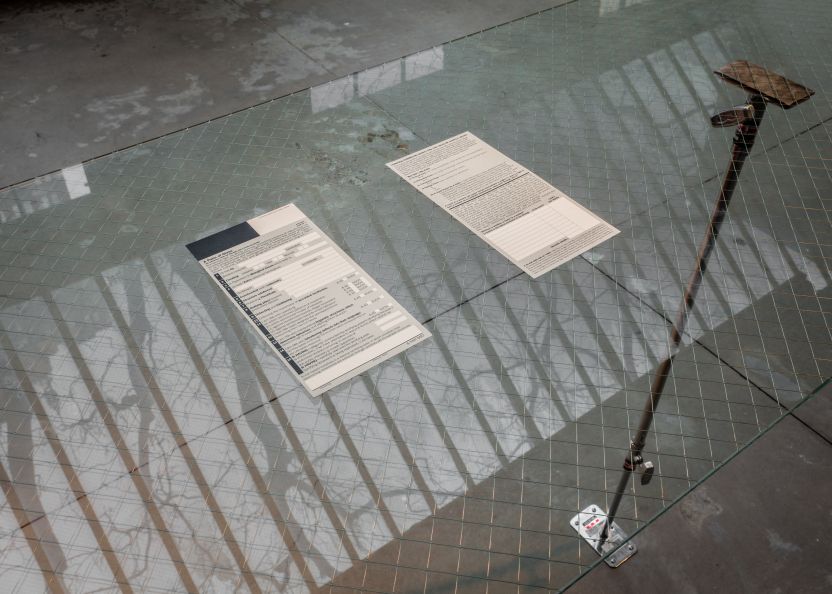

OUR NARRATOR on a stage consisting of six panes of safety glass cracking underfoot (and presented within an increased necessity to examine brutality closely again):

SCENE ONE:

& WITH THE TENDERNESS OF LEECHES:

OUR NARRATOR:

I sought a soul akin to mine, but I could not find one. I searched every corner of the earth; my perseverance brought no reward. Yet I could not remain alone. Someone had to approve of my character; someone had to have the same ideas as I.

It was morning; the sun rose in all its magnificence on the horizon and before my eyes a young man also arose whose presence made flowers grow as he passed. He approached me and, holding out his hand, said: ‘I have come to you who seek me. Let us bless this happy day.’ But I answered: ‘Go away. I did not call you; I do not need your friendship.’

It was evening; night was beginning to spread the veil of its blackness over nature. A lovely woman, whose form I could only just make out, was exerting a spellbinding influence over me, and looking at me, I said: ‘Come closer, that I may make out clearly the features of your face; for the light of the stars is not strong enough to show them, at this distance.’ Then, with her eyelids lowered, she stepped chastely across the lawn in my direction. As soon as I saw her I said: ‘I see that goodness and justice have dwelt in your heart. We could never live together. Now you admire my beauty, which has distracted more than one; but sooner or later you would repent of having given your love to me; for you do not know my soul. Not that I would ever be unfaithful to you; to her who gives herself to me with such trust and abandon I will give myself with equal trust and abandon; but get this into your head and do not ever forget it: wolves and lambs do not look lovingly at one another.’

What did I need, I who had rejected with such disgust the loveliest of mankind! What I needed I could not say. I was not yet in the habit of keeping strict note of my mental phenomena according to the methods recommended by philosophy.

I sat down on a rock, by the sea. A ship had just set all sails to leave those parts: an impenetrable point had just appeared on the horizon and was gradually approaching, driven on by the gust of wind, and growing rapidly in size. The tempest was about to begin its assaults, already the sky was growing dark, until it became black, almost as hideous as the heart of man.

The ship, which was a big man-of-war, had just dropped anchor to avoid being swept on to the rocks. The wind was whistling furiously from all directions, tearing the sails to shreds. Thunder was bursting amid the lightning flashes, and could not drown the sounds of lamentations heard in this house with no foundations, this moving sepulchre. The rolling of those watery masses had not yet broken the anchor-chains; but their buffetings had opened a way for the water in the ship’s sides. It was an enormous breach; the pumps are unable to bail out the flood of salt water which comes foaming and beating down on the bridge like mountains. The ship in distress fires the cannon to give the alarm; but it sinks slowly...majestically.

He who has not seen a ship sinking in a hurricane, and flashes of lightning alternating with the deepest darkness, while those who are in it are overwhelmed with the despair you know of, that man knows nothing of the accidents of life. At last a universal wail of immense pain goes up from the sides of the ship, while the sea redoubles its dreadful attacks. It is the cry of men who have no strength left. Each man wraps himself in the cloak of resignation and leaves his fate in God's hands. They huddle up together like a flock of sheep. The ship in distress fires the cannon to give the alarm; but it sinks slowly...majestically.

The pumps have been going all day long. Vain efforts. Night, thick and implacable, has come to put the finishing stroke to this gracious spectacle. Everyone says inwardly that once he is in the water he will not be able to breathe; for as far as he can recall, he knows of no fishes among his ancestors. But he resolves to hold his breath for as long as possible, to prolong his life by two or three seconds; that is the avenging irony with which he wishes to confront death. The ship in distress fires the cannon to give the alarm; but it sinks slowly...majestically.

He does not know that the sinking vessel causes a powerful circumvolution of waves; that murky undercurrents have joined the troubled waters and a force from below, the counterpart of the tempest raging above, is making the movements of the element nervous and spasmodic. Thus, despite the store of composure which he is gathering in advance, the future drowned man, after mature consideration, ought to feel happy if he can even prolong his life amid the eddying deeps by the space of half a normal breath for good measure. He will not be able to flout death, which is his supreme wish. The ship in distress fires the cannon to give the alarm; but it sinks slowly...majestically.

I am wrong. It is no longer firing its cannon, it is not sinking. No! the cockle shell has been completely engulfed. O heaven! how can one go on living after experiencing such delights! I had just been given the privilege of witnessing the death-throes of several of my fellow-beings. Minute by minute I followed the vicissitudes of their agony. Now the bawling of some old woman, mad with fear, was at a premium. Now only the yelling of a child at breast prevented the steering orders from being heard. The vessel was too far away for me to hear distinctly the sound of groans carried on the gust; but I brought it nearer by an act of will, and the optical illusion was perfect.

Every quarter of an hour, when a gust stronger than the others, uttering its mournful tones above the cries of fear-stricken petrels, broke up the ship in a longitudinal crunching movement, increasing the laments of those about to be offered as sacrifices to death, I dug a sharp metal point deep in my cheek and secretly thought: They are suffering more! In this way I at least had a point of comparison.

I apostrophized them from the shore, hurling threats and imprecations at them. It seemed that they ought to hear me! It seemed that my hatred and my words, over-leaping the distance, were abolishing the physical laws of sound and distinctly reaching their ears which had been deafened by the roaring of the angry ocean. It seemed that they ought to think of me, and breathe vengeance in impotent rage!

From time to time I looked up towards the cities slumbering on firm land; and seeing that nobody suspected that a ship was going to sink some miles from shore, with birds of prey for a crown and ravenous aquatic giants for a pedestal, I took courage again and hope returned to me: so I was certain of their destruction! They could not escape! To make assurance doubly sure, I had gone to fetch my double-barreled rifle so that if some survivor was tempted to approach the rocks of the shore to escape imminent death, a bullet in the shoulder would shatter his arm and prevent him from carrying out his plan.

At the moment of the tempest's greatest fury, I saw a head, its hair standing on end, frantically bobbing up and down in the water. The swimmer was swallowing litres of water and, buoyed up like a cork, was sinking into the deep. But soon he would reappear, his hair streaming, his eyes riveted on the shore; he seemed to be challenging death. His composure was admirable. A huge bleeding wound caused by the jagged point of a hidden reef had gashed his brave and noble face. He could not have been more than sixteen years old; for the peach-like down on his upper lip could just be made out by the flashes which lit up the night. And now he was only two hundred yards from the cliff. I could easily get a clear view of him. What courage! What indomitable spirit! How the determined set of his head seemed to flout destiny as he vigorously cleaved the waves which did not easily give way before him. I had made up my mind in advance. I owed it to myself to keep my promise; the last hour had tolled for all; none must escape. That was my resolution; nothing would change it...a sharp sound was heard, the head went down, and did not reappear.

I did not take much pleasure in this murder as one might think; it was precisely because I was sated with all this killing which I was doing out of pure habit; one cannot do without it, but it provides only a slight enjoyment. The sense is dulled, hardened. What pleasure could I feel at the death of this human being when there were more than a hundred who, once the ship had gone down, would provide me with the spectacle of their deaths and their last struggle against the waves? This death did not even have the appeal of danger; for human justice, rocked by the hurricane of this dreadful night, was slumbering within doors, a few steps from me.

And now that the years are weighing down on me, I can sincerely speak this simple and solemn truth: I was never as cruel as men afterwards said I was; whereas many times their persistent acts of wickedness went on wreaking havoc for years on end. Then my rage knew no bounds; I was possessed by fits of cruelty and I became fearsome to anyone who came within sight of my haggard eyes--that is, if he was of my race. If it was a horse or a dog, I let it pass: have you heard what I have just said?

Unfortunately, on the night of that tempest, one of those fits had come upon me, my reason had abandoned me (for normally I was just as cruel, but more cautious); everything which fell into my hands that night would have to die; I am not claiming that this excuses my misdeeds.

The fault is not entirely with my fellow-creatures. I am only stating things as they are while I wait for the last judgment, which makes me scratch my head in advance...What does the last judgment matter to me! My reason never abandons me, as I have just claimed in order to deceive you. And when I commit a crime, I know what I am doing: I did not want to do something else!

Standing on the rocks as the hurricane lashed my hair and my cloak, I watched ecstatically as the tempest's might bore down on a ship beneath a starless sky. I followed all the peripeteias of this drama, from the moment when the vessel dropped anchor until the moment when it was swallowed up, a deadly garment which dragged into the bowels of the sea all those who had put it on as a cloak.

But the moment was approaching when I myself was to be involved in these scenes of nature in tumult. When the place where the vessel had been struggling clearly showed that it had gone to spend the rest of its days on the ground-floor of the sea, some of those who had been carried off by the waves began to reappear on the surface. They held one another around the waist, in twos and threes; it was a good way of not saving their lives; for their movements became entangled and they went down like leaking jugs.

What is this army of sea-monsters cleaving the water so rapidly? There are six of them; their fins are strong and they are forcing their way through the heaving seas. The sharks soon make an omelette without eggs of all the human beings moving their limbs on the unstable continent; they share it out according to the law of the strongest. Blood mixes with water, and the water mixes with the blood. Their wild eyes light up well enough the scene of carnage.

Yet what tumult is that there, yonder on the horizon? You would take it for a whirlwind approaching! What flailing! I see what it is. A huge female shark is coming to partake of the pate de foie of duck and cold beef. She is wild with anger; for when she arrives, she is starving. A struggle ensues between her and the other sharks, fighting over the few palpitating limbs which are floating here and there dumbly on the surface of the red cream. She snaps and bites to the right and to the left, wounding fatally all that she gets her teeth into. But there are still three living sharks around her and she is obliged to turn in all directions to foil their tricks.

With increasing emotion, such as I have never felt, I follow this new kind of naval battle from the shore. I am staring at the courageous female shark, whose teeth are so strong. I no longer waver, but shoulder the rifle and, with my customary skill, lodge the second bullet in the gills of one of the sharks as it appeared above the waves. Two sharks remain who, seeing this, go to it all the more eagerly. From the top of the rock I, with briny saliva, fling myself into the sea and swim towards the pleasantly-coloured carpet, holding in my hand the steel dagger which I always carries with me. From now on each shark has an enemy to deal with.

I advance on my weary adversary and, taking my time, bury the sharp blade of my knife in its belly. The moving citadel easily accounts for her last adversary. I am now in the presence of the female shark I have saved. We look into each other's eyes for some minutes, each astonished to find such ferocity in the other's eyes. We swim around keeping each other in sight, and each one saying to themself: 'I have been mistaken; here is one more evil than I.’

Then by common accord we glide towards one another underwater, the shark using its fins, me cleaving the waves with my arms; and we hold our breath in deep veneration, each one wishing to gave for the first time upon the other, our living portrait. When we are three yards apart we suddenly and spontaneously fall upon one another like two lovers and embrace with dignity and gratitude, clasping each other as tenderly as brother and sister. Carnal desire follows this demonstration of friendship. My sinewy thighs press tightly against the monster's viscous flesh, like two leeches; and arms and fins are clasped around the beloved object, while our throats and breasts soon form one glaucous mass amid the exhalations of the seaweed; amidst the tempest which was continuing to rage; by the light of lightning-flashes; with the foaming waves for marriage-bed; borne by an undersea current and rolling on top of one another down into the unknown deeps, we joined in a long, chaste and ghastly coupling!...At last I had found one akin to me...from now on I was no longer alone in life...! Her ideas were the same as mine...I was face to face with my first love!

SCENE TWO:

& WITH THE TENDERNESS OF LICE:

OUR NARRATOR:

I have had a grave built, forty square leagues in area, and of a corresponding depth. There, in its foul virginity, lies a living mine of lice. It fills the bottom of the pit, and thence it spreads out in wide thick veins in all directions.

This is how I built this mine: I pulled a female louse out of the hair of man. I slept with it for three consecutive nights, then I threw it into the pit. Destiny saw to it that human fecundation, which would have been impossible in other similar cases, was successful this time; and after a few days, thousands of monsters, crawling in a compact mass of matter, first saw the light of day. This hideous mass became more and more immense in time, acquiring the liquid property of mercury, and branched out into several groups which at the moment sustain themselves by eating one another (the birth-rate being higher than the mortality- rate), unless I throw them as fodder a new-born bastard whose mother wished its death, or the arm of some young girl which I cut off during the night, after drugging her with chloroform.

Every fifteen years, the generations of lice which live off men diminish noticeably and infallibly predict the approaching era of their complete destruction. For man, more intelligent than his enemy, has managed to conquer him. Then, with an infernal spade which increases my strength, I extract blocks of lice from this inexhaustible mine, break them up with axe-blows, and transport into the arteries of cities. There they dissolve on contact with human temperature as in the first days of their formation in the winding galleries of the underground mine, they dig down into the gravel and spread like little streams into the dwelling-places of men like malign spirits. The watchdog gives a low bark, for it seems to him that a legion of unknown beings is penetrating the pores of the walls, bringing terror to the bed of sleep. Perhaps, at least once in your life, you have heard one of these wailing, prolonged barks. With his feeble eyes he tries to pierce the darkness of the night; for all this passes the understanding of his dog-brain. This humming irritates him, he feels he has been betrayed.

Millions of the enemy swoop down thus on each city, like clouds of locusts. That will be enough for fifteen years. They will fight against man, and inflict sharp wounds on him. After this period, I will send others.

When I am smashing the block of living matter, it may happen that one fragment is denser than another. Its atoms are striving furiously to break off from the agglomeration and go and torment mankind; but the cohesion of the whole is such that it resists all their efforts. In a supreme convulsion, they make such an effort that the block, unable to scatter its living elements, soars right into the air as if set off by gunpowder, then falls again, and buries itself firmly in the ground. Sometimes, a pensive peasant sees an aerolith vertically rending space, moving downwards towards a cornfield. He does not know where the stone comes from. Now you have, clearly and succinctly, the explanation of the phenomenon.

If the face of the earth were covered with lice as the seashore is covered with grains of sand, the human race would be destroyed, a prey to dreadful pain. What a sight! With me, motionless on my angel wings in the air to contemplate it!

There are moments when I, with my louse-ridden hair, cast wild staring looks at the green membranes of space; for I believes I hear, somewhere ahead, the ironic hoots of a phantom. I stagger and bows my head; what I have heard is the voice of conscience. Then with the speed of a madman I rush out of the house, take the first direction my wild state suggests and bound over the rough plains of the countryside. But the yellow phantom never loses sight of me, pursuing me with equal speed.

Sometimes on stormy nights, while legions of winged octopi, which look like ravens at a distance, hover above the clouds, moving ponderously towards the cities of men, their mission to warn them to change their conduct; on such nights I see two things pass by, lit up by the flashes of lightning, one after another; and wiping a furtive tear of compassion which flows from my frozen eye, I shout out: 'Yes, he certainly deserves it; it is only justice being done.' Having said that I reassume my grim attitude and continues to watch, trembling nervously, the manhunt, and the big lips of the shadowy vagina from which immense dark spermatozoids flow unceasingly like a river and then soar up into the lugubrious ether, hiding all nature with the vast span of their bat's wings, including the solitary legions of octopi, now gloomy at the sight of these dumb inexpressible fulgurations.

But all the time the steeplechase between these two tireless runners is going on, and the phantom hurls torrents of fire from his mouth on to my singed back. If, while I am accomplishing this duty, I come upon pity trying to bar my way, I give in disgustedly to her supplications, and allows the man to escape. The phantom makes a clicking sound with its tongue, as if to tell itself that it is giving up the chase, and then returns to its kennel for the time being. His is the voice of the condemned: it can be heard even in the furthest layers of space; and when its dreadful shrieking penetrates the human heart, then man would prefer, as the saying goes, to have death as his mother than remorse as his son.

Conscience judges our most secret thoughts and acts severely, and is never wrong. Being powerless to prevent evil, it never ceases to hunt man down like a fox, especially in the hours of darkness. Avenging eyes, which ignorant science calls meteors, shed a livid flame of light, revolving on themselves as they pass and uttering mysterious words...which he understands! Then his bed is battered by the convulsions of his body, burdened by the weight of insomnia, and he hears the sinister breathing of night's vague rumours.

The angel of sleep himself, having been struck a mortal blow on the forehead from a stone whose thrower is unknown, abandons his task and re-ascends towards heaven.

Now this time I am here to defend man; I, the scorner of all virtues; I, whom the Creator has never forgotten since the day when I knocked from their pedestal the annals of heaven where by some infamous intrigue his power and his eternity had consigned, and I applied my four hundred suckers to his armpits, making him utter dreadful cries.

They changed into vipers as his mouth uttered them and went and hid in the undergrowth, among ruined old walls, on the watch by day, on the watch by night. These cries crawled, endowed with countless rings and a small flat head, and wickedly gleaming eyes. They have vowed to stop at the sight of human innocence. But when men in their innocence are out walking in the tangles of the maquis, on steep slopes or on the dunes of the sand, they soon change their mind, something makes them want to go back. If, that is, there is still time; for, at times, men notice the poison is creeping along the veins of their leg by means of an almost imperceptible bite, before they have had time to turn back and escape into the open.

Thus it is that the Creator, admirably cool even in the presence of the most appalling sufferings, extracts from the very breasts of men the germs which are harmful to those who live on earth.

Imagine his astonishment when I changed into an octopus coming towards him with my eight monstrous tentacles, each one of them which was a solid lash which could easily have encompassed a planet's circumference.

Caught unawares, he struggled for some moments against the viscous embrace, which was getting tighter and tighter...I feared some foul trick on his part; having fed copiously on the globules of his sacred blood, I suddenly pulled away from his majestic body, and went and hid deep in a cave, which has been my abode since then.

After many fruitless searches, he was still unable to find me. That was a long time ago; but I think he knows now where I live; he is wary of entering; the two of us live like monarchs of neighbouring lands, who know their respective strengths, cannot defeat one another, and are weary of the useless battles of the past. He fears me, and I fear him; each of us, though undefeated, has felt the savage blows of his adversary, and it is stalemate.

However, I am ready to take up the struggle again whenever he wishes. But I advise him not to wait for the right moment for his hidden schemes. I will always be on guard, I will always keep my eye on him; let him not visit the earth with conscience and its torments. I have taught men what weapons to use to combat it successfully. They have not yet grown accustomed to conscience; but you know that, for me, it is as the wind-blown straw. And I treat it as such.

If I wanted to use the opportunity to indulge in subtle poetic discussion, I would add that a straw is more to me than conscience; for straw is useful for the ox chewing the cud, whereas conscience has only its claws of steel to show. These claws suffered a painful setback the day they came before me. As conscience had been sent by the Creator, I did not think fit to allow it to bar my way. If it had come to me with the modesty and humility proper to its rank (which it ought never to have tried to rise above), then I would have listened to it. I did not like its pride.

I stretched out my hand and ground its claws with my fingers; they fell as dust to the ground, beneath the pressure of this new kind of mortar. I stretched out my other hand and pulled off its head. Then I hunted that woman out of my house with a whip, and I never saw her again. I have kept her head as a souvenir of my victory.

Gnawing the skull of the head which I held in my hand, I stood on one leg, like a heron, beside a precipice on the side of a mountain. I was seen going down the valley, while the skin of my breast remained as still and calm as the lid of a tomb!

Gnawing the skull of the head which I held in my hand, I swam in the most dangerous gulfs, along by lethal reefs, and I dived deeper than any current, to witness, as a stranger, the combats of sea-monsters; I swam so far the shore that it was out of my piercing sight; and hideous cramps, with their paralysing magnetism, prowled around my limbs as they cleaved the waves with their forceful movements, but they did not dare to approach. I was seen returning safe and sound to the beach, while the skin of my breast remained as still and calm as the lid of a tomb!

Gnawing the skull of the head which I held in my hands, I mounted the steps of a high tower. I reached the platform, high above the ground. I looked out over the countryside and the sea; I looked at the sun, the firmament; kicking hard against the granite which did not give way, I challenged death and divine vengeance with a supreme howl of contempt and then hurled myself like a paving-stone into the mouth of space. Men heard the painful resounding thud which occurred as the head of conscience, which I had abandoned as I fell, hit the ground. I was seen descending, slow as a bird, borne on an invisible cloud, and picking up the head, so that I could force it to witness a triple crime, which I was to commit that day, while the skin of my breast remained as still as the lid of a tomb!

Gnawing the skull of the head which I held in my hands, I made for the place where the guillotine is. Beneath the blade, I placed the smooth and delicate necks of three young girls. Executor of fine works, I released the rope with the apparent deftness of a lifetime's experience; and the triangular blade, falling obliquely, lopped off three heads which were looking at me sweetly. Then I put my own head beneath the weighty razor, and the executioner prepared to do his duty. Thrice the blade slid along the grooves with renewed force; thrice, my material carcass was moved to the very depths, especially at the base of my neck, as when one dreams that one has been crushed to death beneath a collapsing house. The stunned crowd let me pass and leave the gloomy square. It saw me opening up with my elbows its undulating waves, carrying the head straight in front of me, while the skin of my breast remained as still and as calm as the lid of a tomb!

SCENE THREE:

& WITH THE TENDERNESS OF LEECHES:

OUR NARRATOR:

Throughout my life, I have seen narrow-shouldered men, without a single exception, committing innumerable stupid acts, brutalizing their fellows, and perverting souls by all means. They call the motive for their actions fame.

Seeing these spectacles, I wanted to laugh like the others but I found that strange imitation impossible. I took a knife with a sharp steel cutting-edge on its blade and slit my flesh where the lips join. For a moment I believed I had achieved my object. I looked in a mirror at this mouth disfigured by an act of my own will. It was a mistake! The blood flowing from the two wounds prevented me from discerning whether the laugh really was the same as the others’. But after comparing them for a few moments I saw clearly that my laugh did not resemble that of human beings. I was not laughing at all.

One should let one's nails grow for a fortnight. Oh! How sweet it is to brutally snatch from his bed a child with no hair yet on his upper lip, and, with eyes wide open, to pretend to suavely stroke his forehead, brushing back his beautiful locks! Then, suddenly, at the moment when he least expects it, to sink one's long nails into his tender breast, being careful, though, not to kill him; for if he died, there would be no later viewing of his misery. Then, you must drink the blood, licking the wounds, as he cries. Nothing could taste better than his blood, warm and fresh as I have described, if it weren’t for his tears, bitter as salt.

Have you ever tasted your own blood, when you’ve accidentally cut your finger? Tasty, isn't it? Or tasted your own tears? Tasty, aren't they? For they taste of vinegar. A taste reminiscent of the tears of your true love, except a child's tears are so much more pleasing to the palate. He is incapable of deceit, for he does not yet know evil.

So, since your blood and tears do not disgust you, go ahead, feed confidently on the adolescent's tears and blood. Blindfold him, while you tear open his quivering flesh; and, after listening to his resplendent squeals for a few hours, similar to the shrieks of death one hears from the throats of the mortally wounded on battlefields, then, running faster than an avalanche, fly back in from the room next door, pretending to rush to his rescue. Untie his hands, with their swollen nerves and veins, and restore sight to his distraught eyes by licking his tears and blood. Oh, what a genuine and noble change of heart!

O child, who has just undergone such cruel torture, who could have ever committed such an unspeakable crime upon you! You poor soul! The agony you must be going through! And if your mother were to know of this, she would be no closer to death, so feared by evildoers, than I am now. Alas! What, then, are good and evil? Might they be one and the same thing, by which in our furious rage we attest our impotence and our passionate thirst to attain the infinite by even the maddest means? Or might they be two separate things? Yes... they'd better be one and the same... for, if not, what shall become of me on the Day of Judgment? Forgive me, child. Here before your noble and sacred eyes stands the man who crushed your bones and tore off the strips of flesh dangling from various parts of your body. Was it a frenzied inspiration of my delirious mind, was it a deep inner instinct independent of my reason, such as that of the eagle tearing at its prey, that drove me to commit this crime? And yet, as much as my victim, I suffered! Forgive me, child. Once we are freed from this transient life, I want us to be entwined for evermore, becoming but one being, my mouth fused to your mouth. But even so, my punishment will not be complete. So you will tear at me, without ever stopping, with your teeth and nails at the same time. I will adorn and embalm my body with perfumes and garlands for this expiatory holocaust; and together we shall suffer, I from being torn, you from tearing me... my mouth fused to yours. O blond-haired child, with your eyes so gentle, will you now do what I advise you? Despite yourself, I wish you to do it, and you will set my conscience at rest.

And in saying this, you will have wronged a human being and be loved by that same being: therein lies the greatest conceivable happiness. Later, you could take him to the hospital, for the crippled boy will be in no condition to earn a living. They will proclaim you a hero, and centuries from now, laurel crowns and gold medals will cover your bare feet on your ancient iconic tomb.

On my daily walk I used to pass through a narrow street every day. Every day a slim ten-year-old girl would follow me along the street, keeping a respectful distance, looking at me with sympathetic, curious eyes. She was big for her age, and had a well-shaped body. Long, black hair, parted on her head, fell in separate tresses on to shoulders like marble.

One day she was following me as usual; the sturdy arms of a woman of the people caught her by the hair, like a whirlwind catches a leaf, and slapped her twice, brutally, on her proud, silent face. Then she brought that straying consciousness back home. I tried in vain to appear unconcerned; she never failed to pursue me, though her presence had by now become irksome. When I took a different route, she would stop, struggling violently to control herself, at the end of the street, standing still as the statue of silence, and she would not cease looking before her until I was out of sight.

One day this girl went on ahead of me in the street, and fell into step with me. If I walked faster to pass by her, she almost ran to keep the same distance between us. But if I slowed down so that there would be a large space between us, she slowed down too, and did so with all the grace of childhood. When we reached the end of the street, she slowly turned round barring my way. There was no time no for me to slip away; now I stood before her. Her eyes were swollen and red. It was easy to see that she wanted to speak to me, but did not know how to go about it. Her face suddenly turning pale as a corpse, she asked me: ‘Would you be so kind as to tell me what time it is?’ I told her I did not have a watch and walked rapidly away.

And since that day, child of the troubled and precocious imagination, you have not seen in your narrow street the mysterious young man whose heavy sandals could be heard clattering along those winding roads. The appearance of this blazing comet will never be repeated; the mournful object of your fanatical curiosity will no longer flash on the facade of your disappointed observation. And you will often think, too often, perhaps always, of him who did not seem to be worried about the good and evil of this life, who went haphazardly away — with his face horribly dead, his hair standing on end, with a tottering gait, his arms swimming blindly in the ironic waters of ether, as if he were seeking there the bleeding prey of hope, continually buoyed up, through the immense regions of space, by the implacable snow-plough of fatality. You will see me no more, and I will no longer see you!...

Who knows? Perhaps this young girl was not what she appeared to be. Perhaps boundless cunning, eighteen years’ experience and the charm of vice were hidden beneath her innocent appearance. Young sellers of love have been known to leave the British Isles gaily behind them and cross the channel. They spread their wings, whirling in golden swarms in the Parisian light; and whenever they were seen, people would say: ‘they are no more than ten or twelve years old’. But in reality they were twenty. Oh, if this supposition be true, cursed be the windings of that dark street! Horrible! horrible! the things that happen there.

I think her mother struck her because she was not plying her trade skillfully enough. It is possible that she was only a child and, in that case, the mother is even more guilty. For my part, I refuse to believe this supposition, which is only a hypothesis and I prefer to see and to love, in this romantic character, a soul revealing itself too soon...

Ah, young girl, I charge you not to reappear before me, if ever I return to that narrow street. It could cost you dear! No! No! I, generous enough to love my fellows! I have resolved against it since the day of my birth! They do not love me! Worlds will be destroyed, granite will glide like a cormorant on the surface of the waves before I touch the infamous hands of another human being. Back...back with that hand! Young girl, you are no angel, you will become like other women after all.

No, no, I implore you, do not reappear before my frowning squinting eyes. In a moment of distraction I might take your arms and wring them like linen which is squeezed after washing, or break them with a crack like two dry branches and then forcibly make you eat them. Taking your head between my hands with a gentle, caressing air, I might dig my greedy fingers into the lobes of your innocent brain — to extract, with a smile on my lips, a substance which is good ointment to bathe my eyes, sore from the eternal insomnia of life.

I might, by stitching your eyelids together, deprive you of the spectacle of the universe, and make it impossible for you to see your way; and then I should certainly not act as your guide. I might, raising your virgin body in my iron arms, seize you by the legs and swing you around me like a front, concentrating all my strength as I described the final circle, and hurling you against the wall.

Each drop of your blood would spurt onto a human breast, to frighten men and to set before them an example of my wickedness. They will tear shreds and shreds of flesh from their bodies; but the drop of blood remains, ineffaceable, in the same place, and will shine like a diamond.

Do not be alarmed. I will instruct half a dozen servants to keep the venerated remains of your body and to protect them from the ravenous hunger of the dogs. No doubt the body has remained stuck to the wall like a ripe pear and has not fallen to the earth; but a dog can jump extremely high, if one is not careful...

SCENE FOUR:

& WITH THE TENDERNESS OF RAVENS:

OUR NARRATOR:

Behold the madwoman dancing along, with a vague memory of something in her mind.

Children chase after her and throw stones at her, as if she were a blackbird. She brandishes a stick and makes as if to chase them, then continues on her way. She has left a shoe behind her on the path, and does not notice it. Long spiders' legs move on her nape; they are none other than her hair. Her face no longer looks like a human face, and she bursts into fits of laughter, like a hyena. She utters scraps of sentences in which, when they are put together, few would be able to find any clear meaning. Her dress has holes in several places and moves jerkily to show her bony and mud-bespattered legs. She moves forward in a daze, her youth, her illusions and her past happiness, which she glimpses through her ruined mind's haze, all swept along like a poplar leaf by the whirl of unconscious powers. She has lost her former grace and beauty; the way she walks is mean and low, her breath reeks of gin. If men were happy on this earth, it would surprise us. The madwoman reproaches no one, she is too proud to complain, and she will die without revealing her secret to those who are interested in her, but whom she has forbidden even to speak to her.

Children chase after her and throw stones at her, as if she were a blackbird.

After many years of barrenness, Providence blessed her with a child, a girl. For three whole days she knelt in churches and never ceased thanking Him who had at last granted her wishes. With her own milk she suckled the child, who meant more to her than her own life. She was endowed with all the good qualities of body and soul, and she grew quickly. She would say to her mother: "I would like to have a little sister to play with; ask the good Lord to send me one; and I, in return, will wreathe a garland of violets, mint, and geraniums."

Her answer was to sit her on her lap, press her to her breast and kiss her lovingly. She was already interested in animals and used to ask why it was that the swallow merely brushed against the cottages of men with its wings, without ever daring to enter. But the mother would put her finger on the child’s mouth, as if to tell her to keep silent on this grave questions, the rudiments of which she did not wish to explain to her and perhaps over-excite her childish imagination with too vivid a sensation; and she was anxious to change the subject, which is a painful one for every being who belongs to the race which has imposed its unjust dominion on all the other animals of creation.

Whenever the child spoke to her of the graves in the cemetery, saying how there one could breathe the pleasant perfumes of cypresses and immortelles, the mother was careful not to contradict her; but she said to her that it was the town where the birds lived, that they sang there from morning till dusk, that the graves were their nests where, lifting up the gravelids, they slept at night with their family. And the mother sewed all the pretty little clothes she wore, as well as the lace-dress, with its thousand arabesques, which was reserved for Sundays.

In summer, the meadows felt the gentle pressure of her steps when she ventured out with her silk net on the end of a rush, chasing the wild, free hummingbird, and butterflies with their frustrating, zig-zagging motion. The mother asked: "What have you been doing, you little scamp, your soup has been waiting for you for over and hour?" But the girl exclaimed as she flung her arms around her mother’s neck that she would never go back there. The next day she was off again, skipping over the daisies and the mignonettes; among the sunbeams and the whirling flight of the ephemera; knowing only life's prismatic glass, none of its rancour yet; glad to be no bigger than the bluetit; innocently teasing the warbler, which does not sing as well as the nightingale; slyly putting her tongue out at the nasty raven which was looking at her in a fatherly way; graceful as a young cat in her movements.

But the time was coming near when she would unexpectedly have to say goodbye to life's enchantments, abandoning forever the company of turtledoves, grouse and greenfinches, the babbling of the tulip and the anemone, the counsel of the marsh-grass, the sharp wit of the frogs, the coolness of the streams.

I was passing with my bulldog; I saw a young girl sleeping in the shade of a plane-tree, and at first I took her for a rose. It is impossible to say which came first to my mind: the sight of this young girl, or the resolution which followed. I undressed rapidly, like a man who knows what he is going to do. Stark naked, I flung himself upon the girl, lifting her dress to commit an assault upon modesty...in broad daylight...that did not worry me, you may be sure. But let us not dwell on this impure act.

Discontented in mind, I hurriedly got dressed again, cast a prudent glance towards the dusty pathway where no one was walking, and ordered the bulldog to strangle a blood-bespattered young girl with a snap of his jaws. I pointed out to the mountain-dog the place where the suffering victim was breathing and shrieking, and withdrew from the scene, not wishing to be present as the sharp teeth enter the pink veins. It seemed to the dog that the execution of this order was harsh. He thought he was being asked to do what had already been done, and contented himself, this monstrous snouted wolf, with violating in turn the virginity of this delicate child. From her torn belly the blood flowed again along her legs, over the meadow... Her moans joined the whining of the animal.

The young girl gave him the golden cross which adorned her neck, so that he would spare her. She had not dared to show it to the wild eye of I who had first thought of taking advantage of the weakness of her age. But the dog knew well that if he disobeyed his master, a knife-thrust from my sleeve would open up his entrails without a word of warning. I heard the agonized cries of pain, and was astonished that the victim was so tenacious of life that she was not already dead.

I approached the sacrificial altar and saw the behaviour of his bulldog, gratifying his base instincts, rising above the young girl, as a ship-wrecked man raises his head above the waves.

I kicked him and cut out one of his eyes. The maddened bulldog fled across the countryside, dragging after him along a stretch of the road, which though it is short, is still too long, the body of the young girl which is hanging from him and which only comes free as a result of the jerky movements of the fleeing dog; but he is afraid of attacking his master, who will never set eyes on him again.

I took an American penknife from my pocket, consisting of twelve blades which can be put to different uses. He opened the angular claws of this steel hydra; and armed with a scalpel of the same kind, seeing that the green of the grass had not yet disappeared beneath all the blood which had been shed, I prepared, without blenching, to dig my knife courageously into the unfortunate child.

From the widened hole I pulled out, one after one, the inner organs; the guts, the lungs, the liver and at last the heart itself are torn from their foundations and dragged through the hideous hole into the light of day.

I notice that the young girl, a gutted chicken, has long been dead. I stopped my ravages, which had gone on until then with increasing eagerness, and let the corpse sleep, again, in the shade of the plane-tree.

SCENE FIVE:

& WITH THE TENDERNESS OF PARASITES:

OUR NARRATOR:

I am filthy. I am riddled with lice. Hogs, when they look at me, vomit. My skin is encrusted with the scabs and scales of leprosy, and covered with yellowish pus. I know neither the water of rivers nor the dew of clouds. An enormous, mushroom with umbelliferous stalks is growing on my nape, as on a dunghill.

Sitting on a shapeless piece of furniture, I have not moved my limbs now for four centuries. My feet have taken root in the ground; up to my belly, they form a sort of tenacious vegetation, full of filthy parasites; this vegetation no longer has anything in common with other plants, nor is it flesh. And yet my heart beats. How could it beat, if the rottenness and miasmata of my corpse (I dare not say body), did not nourish it abundantly?

A family of toads has taken up residence in my left armpit and, when one of them moves, it tickles. Mind one of them does not escape and come and scratch the inside of your ear with its mouth; for it would then be able to enter your brain. In my right armpit there is a chameleon which is perpetually chasing them, to avoid starving to death: everyone must live. But when one party has completely foiled the cunning tricks of the other, they like nothing better than to leave one another in peace and suck the delicate fat which covers my sides: I am used to it.

An evil snake has eaten my verge and taken its place; the filthy creature has made me a eunuch. Oh if only I could have defended myself with my paralysed hands; but I rather think they have changed into logs. However that may be, it is important to state that my red blood no longer flows there.

Two little hedgehogs, which have stopped growing, threw the inside of my testicles to a dog, who did not turn up his nose at it: and they lodged inside the carefully washed epidermis.

My anus has been penetrated by a crab; encouraged by my sluggishness, he guards the entrance with his pincers, and causes me a lot of pain!

Two medusae crossed the seas, immediately enticed by a hope which was not disappointed. They looked attentively at the two fleshy parts which form the human backside, and, clinging on to their convex curve, they so crushed them by constant pressure that the two lumps of flesh have disappeared, while two monsters from the realm of viscosity remain, equal in color, shape, and ferocity. Do not speak of my spinal column, as it is a sword...Yes, yes...I was not paying attention...

SCENE SIX:

& WITH THE TENDERNESS OF CANARIES:

OUR NARRATOR:

On a park bench an individual has come to sit. His hair is tousled and his garments reveal the corrosive effect of prolonged poverty. He has made a hole in the earth with a piece of pointed wood and has filled the palm of his hand with earth. He brought this sustenance to his mouth and then flung it quickly away.

He stood up again and, placing his head against the bench, tried to put his feet up in the air. But as this rope-walking position did not conform to the laws of gravity, he fell back heavily on to the bench again, his arms flailing, his cap covering half his face, and his feet touching the gravel very unsteadily, so that he was more and more precariously poised. He remains in this position for a long time.

I pressed my hand against the railing. I surveyed the surface of the rectangle, with such thoroughness that nothing escaped me. My investigation complete, I looked around near and saw, in the middle of the garden, a man staggering as he practices gymnastics on a bench on which he is endeavoring to steady himself by performing miracles of strength and skill. But what good are the best intentions, in service of a just cause, against the derangements of mental alienation?

I approached the madman and kindly helped him to resume a more normal and dignified position, held out my hand to him, and sat down beside him. I observed that his madness is only intermittent; his fit has passed; he replies logically to all my questions. Is it necessary to relate the meaning of his words? Why should I, at random, reopen, at a given page, with blasphemous eagerness, the folio of human miseries? There is nothing more fruitfully instructive.

Even if I had no true event to recount to you, I would invent imaginary tales and decant them into your brain. But the lunatic did not go mad for his own amusement. And the sincerity of his account is marvelously allied to the reader's credulity.

“My father was a carpenter in the Rue de la Verrerie...on his head be the death of the three Daisies and may the beak of the canary eternally gnaw the axis of his ocular bulb! He had contracted the habit of drunkenness; at those times, after he had been through all the bars, his rage became almost immeasurable, and he would hit out indiscriminately at everything in sight. But soon, in face of his friends' reproaches, he reformed, and became of a taciturn disposition. Nobody could go near him, not even our mother. A secret resentment seethed within him at this notion of a duty, which prevented him from behaving in his own way. I had bought a canary for my three sisters; for my three sisters I had bought a canary. They had put it in a cage above the door, and the passers-by would stop each time to listen to the bird's songs, admire its fleeting grace, and study its clever variations. More than once my father had given orders for us to get rid of the cage and its contents, for he imagined that the canary was mocking him as it offered him its ethereal cavatinas sung with a vocalist's talent. He went and took the cage down from the nail on the wall and slipped off the chair, blinded by rage. A slight graze on his knee was the reward for this attempt. Having spent several seconds pressing a chip of wood on the swollen part, he rolled down his trousers, and, much more cautious this time, took the cage under his arm and went towards the other end of the workshop. There, despite the cries and entreaties of his family (we were very attached to that bird who was, to us, the genius of the house), he crushed the wickerwork cage with his metal heels, while a jointing-plane which he whirled about his head kept those who were present at bay. Chance would have it that the canary did not die straightaway; the flurry of feathers was still alive, despite its bloody mutilation. The carpenter went out, slamming the door behind him. My mother and I tried to prolong the bird's life, which was about to ebb away; it was drawing to its close, and the movement of its wings presented us only the spectacle, the mirror, as it were, of the supreme convulsion, of death-throes. During this time, the three Daisies, perceiving that all hope would soon be gone, by common accord took one another by the hand, and the living chain went and crouched in a corner, pushing a barrel of fat some feet away beside our bitch's kennel. My mother kept on at her task, and was holding the canary in her fingers, trying to revive it with her warm breath. But I was running distraught through all the rooms, knocking against the furniture and the tools. From time to time one of my sisters would show her head at the bottom of the stairs to inquire after the fate of the unhappy bird, and she would then sadly withdraw. The bitch had come out of her kennel, and, as if she understood the enormity of our loss, was licking the dress of the three Daisies in a sterile attempt to comfort them. The canary now had only a few moments to live. One of my sisters in turn (it was the youngest) appeared in the penumbra formed by the rarefaction of light. She saw my mother turn pale, and the bird, having raised its head as the lightning flashed in a final convulsive gesture of its nervous system, fell back again between her fingers, for ever inert. She told her sisters the news. They did not make the slightest murmur of complaint, the slightest whisper. Silence reigned in the workshop. All that could be heard was the occasional sharp creak of the pieces of the cage, which, by virtue of the wood's elasticity, partly sprang back into their original position. The three Daisies did not shed a single tear, their faces lost none of their ruddy freshness. They just stood still. They crawled into the inside of the kennel and stretched out beside each other on the straw; while the bitch, a passive spectator of this procedure, looked at them in amazement. Several times my mother called them; they did not make sound. Tired by the emotions they had just been through, they would probably be asleep! She searched in every corner of the house, but could not see them anywhere. She followed the bitch, who was pulling her by the dress, towards the kennel. This woman knelt down and put her head to the kennel door. The spectacle which presented itself to her, allowing for the unhealthy exaggerations of maternal fear, must have been very harrowing, by my reckoning. I lit a candle and held it out to her; in this way, not a single detail escaped her. She came out of the premature grave, her head covered in straw, and said to me: "The three Daisies are dead." As we could not take them out there, for you must bear well in mind that they were tightly entwined together, I went to the workshop to look for a hammer with which to smash the canine abode. I immediately set about the work of demolition, and the passers-by could well believe if they had any imagination, that we were hard at work in the house. My mother, impatient at the delays which were, however, necessary, was breaking her nails against the wood. At last the operation of negative release came to an end. The kennel, now split, fell apart on all sides, and we took the daughters of the carpenter, one after the other, from the ruins, having had great difficulty in prying them apart. My mother left the country. I never saw my father again. As for me, they say that I am mad and live by begging. What I do know is that the canary no longer sings.”

I approved of this new example which bears out my theories. I consoled the madman with affected words of commiseration and wiped away his tears with my own handkerchief. I took him to a restaurant and we ate at the same table. Then we went off to a fashionable tailor where I bought my protégé clothes fit for a prince. I installed the madman in a sumptuous penthouse apartment. I forced him to accept some money and, taking the chamber-pot from under his bed, puts it on his head. 'I crown you king of the intellect,' I exclaimed with premeditated solemnity. 'At your least call I shall come running; take as much as you wish from my coffers; I am yours, body and soul. At night, you will put the alabaster crown back into its usual place, and you have my permission to use it; but by day, once dawn has lit up the cities, put it back on your head as the symbol of your power. The three Daisies will live again in me, not to mention that I will be a mother to you.' Then the madman took a few steps back, as if he were the plaything of a malicious nightmare; lines of joy crossed his grief-ridden face; he knelt in self-abasement at my feet.

Gratitude, like poison, had entered the crowned madman's heart. He wanted to speak, but his tongue was tied. He leant forward, and fell on the floor.

What was my objective? To find a thoroughly dependable friend, naive enough to obey the least of my commandments. I could not have found a better one, chance had been kind to me. He whom I found on a bench, has not, to my great fortune, since an incident in his youth, been able to distinguish the difference between good an evil.

TO BE REPEATED AS NECESSARY